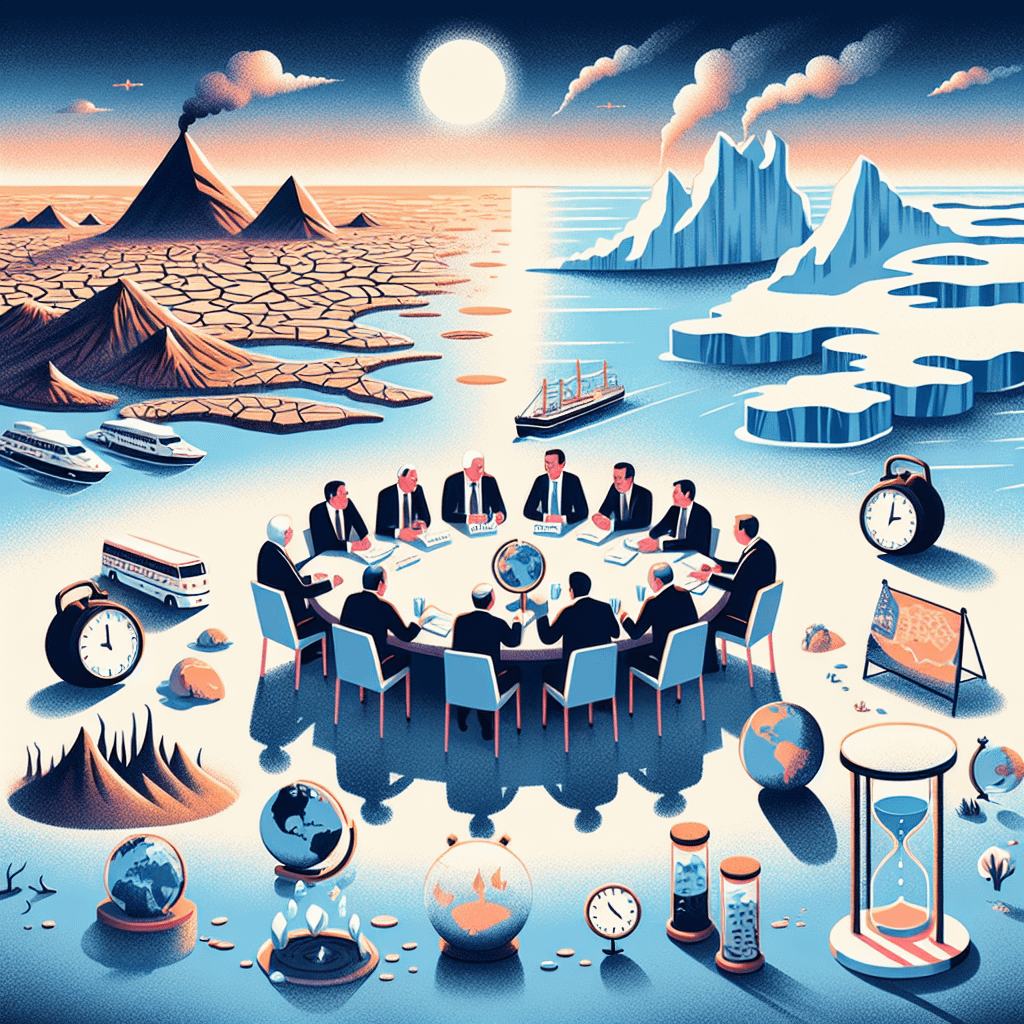

The COP29 climate change conference has come to a close — as per normal it looks like very little will be done.The most urgency that the United Nations can muster is pointing out that “extreme weather events [are] affecting people around the globe.” There is unlikely to be a flurry of national policy action in the wake of COP29. Its achievements, while not insubstantial, are unlikely to move the needle in any significant way.

Some people might think that a 2 C temperature rise doesn’t sound so bad — that a bit warmer world might be nice or that climate change will only affect others. This is a gravely mistaken belief which grossly under appreciates the era of global death and human misery which climate change is ushering in largely unabated.

With only tepid calls for change it is unlikely we will find a way to invest the “trillions of dollars required for countries to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Business-as-usual climate discourse has failed. Understanding the real human deaths caused by carbon emissions could help drive change in climate policy.

Read more:

Cop29: five critical issues still left hanging after an underwhelming UN climate summit in Azerbaijan

Contextualizing climate deaths

In a recent study reviewing more than 180 peer-reviewed articles — which I conducted with fellow researcher Richard Parncutt — we found that climate change could result in around one billion premature deaths by the end of the century unless serious action is taken to reduce emissions.

We refer to the basis of this estimate as the 1,000-ton rule.

The 1,000-ton rule states that a person is killed every time humanity burns 1,000 tons of fossil carbon. A 2 C temperature rise equates to about a billion prematurely dead people over the next century. These people will be killed as a result of a wide range of global warming related climate breakdowns. The carbon budget for 2 C of human-caused warming is about one trillion tons.

These findings were derived from a review of the climate literature that attempted to quantify future human deaths from a long list of mechanisms. This is a staggering prediction of human suffering, though however uncomfortable it may be, it is consistent with diverse evidence and arguments from multiple disciplines.

The old scientific ways of communicating about climate change simply do not work.

Policymakers and scientists have had trouble explaining even relatively basic ideas like climate forcing, the magnitude of a terraWatt, or just what exactly is a ton of carbon dioxide.

It is not necessarily that most people are ignorant, just that these ideas are often too abstract to have any real meaning for most.

Dead bodies, however, we understand. The 1,000-ton rule could serve as a simple, evocative and easily trackable framework for understanding the impact of global carbon emissions in human terms.

Put another way, by focusing on the number of people who will die and not just